Appeals Court: Landlord Can Collect Actual, Not Liquidated, Damages

Appeals Court: Landlord Can Collect Actual, Not Liquidated, Damages

By Christopher R. Vaccaro

Special to Banker & Tradesman

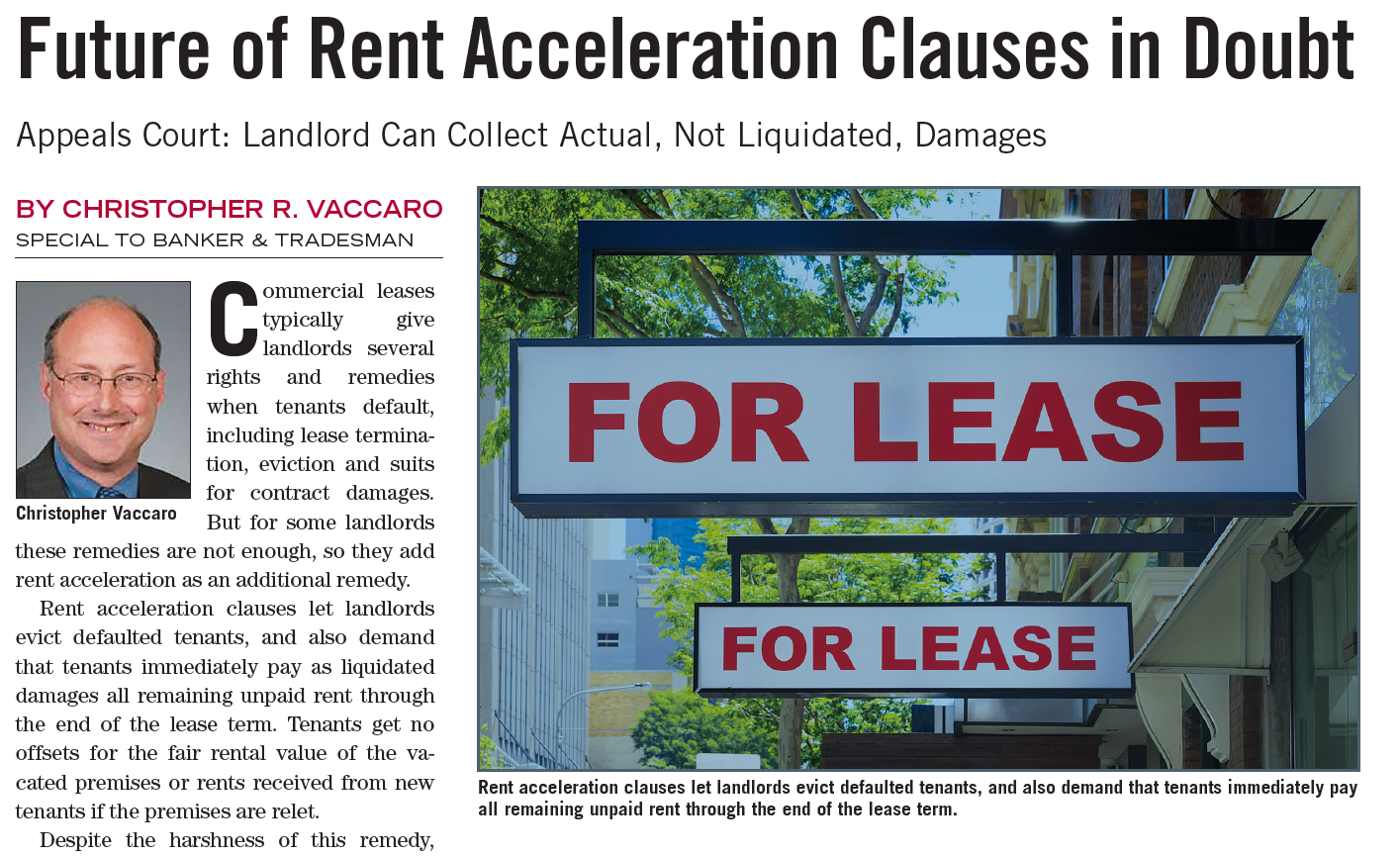

Commercial leases typically give landlords several rights and remedies when tenants default, including lease termination, eviction and suits for contract damages. But for some landlords these remedies are not enough, so they add rent acceleration as an additional remedy.

Rent acceleration clauses let landlords evict defaulted tenants, and also demand that tenants immediately pay as liquidated damages all remaining unpaid rent through the end of the lease term. Tenants get no offsets for the fair rental value of the vacated premises or rents received from new tenants if the premises are relet.

Despite the harshness of this remedy, Massachusetts appellate courts have upheld rent acceleration clauses. For example, in 2007, the Supreme Judicial Court ruled in Cummings Properties, LLC v. National Communications Corp. that a tenant had to pay more than $500,000 in accelerated rent. The Appeals Court in 2019 enforced a rent acceleration clause in Cummings Properties, LLC v. Calloway Laboratories, Inc., requiring a tenant to pay over $1.8 million as liquidated damages.

A tenant narrowly escaped a rent acceleration clause in SpineFrontier, Inc. v. Cummings Properties, LLC, a 2019 Appeals Court decision. The tenant’s lease in that case automatically renewed for five years unless the tenant sent the landlord a termination notice. The tenant emailed its landlord a termination notice, but the lease required that notices be sent by constable, certified mail, or courier service. The landlord claimed that the lease renewed automatically because the emailed termination notice was ineffective, and demanded more than $1.7 million in accelerated rent for the unused renewal term. Fortunately for the tenant, the Superior Court and the Appeals Court ruled that the emailed notice and the tenant’s other communications with the landlord were sufficient to terminate the lease, rendering the landlord’s accelerated rent claim academic.

Last December, the appeals court directly ruled on the validity of a rent acceleration clause in Cummings Properties, LLC v. Hines. Plaintiff Darryl Hines organized the Massachusetts Constable’s Office Inc. (MCO) as a civil process service firm. The firm developed a reputation for using aggressive tactics to serve process and make arrests, which earned Hines and MCO unwanted attention in the local media.

Cummings Files for Further Review

After MCO secured a contract with the Massachusetts Department of Revenue in 2016, it rented space in Woburn from Cummings Properties under a five-year lease. Hines personally guaranteed the lease. Like many of Cummings’s commercial leases, MCO’s lease had a rent acceleration clause. Less than a month into the lease, DOR suspended its contract with MCO, whereupon MCO defaulted on the lease. Cummings sued MCO in District Court for eviction and $74,000 of accelerated rent. Hines signed an agreement for judgment on behalf of MCO, without an attorney’s assistance, awarding Cummings possession and $74,000 in damages. A year later, Cummings signed a new lease with a different tenant. One might think that the new lease would have ended Cummings’s desire to collect accelerated rent, but it did not.

Years after Cummings and MCO signed the agreement for judgment and Cummings secured the new tenant, Cummings sued Hines under his lease guaranty in Superior Court for the accelerated rent. At trial, for reasons that are unclear, Cummings disavowed the agreement for judgment against MCO in District Court when MCO did not have an attorney. Cummings stated that it was pursuing rights against Hines under the lease and the guaranty only. A Superior Court judge entered a judgment against Hines for $82,000, concluding that the accelerated rent clause was enforceable because it was a reasonable estimate of Cummings’s anticipated damages. Hines appealed.

The Appeals Court noted that rent acceleration clauses may be enforceable as liquidated damages provisions as long as they are not punitive, and Hines had the burden of proving that the clause was unenforceable. However, the court observed that Cummings’s acceleration clause allowed it to recover possession of the leased premises, relet it and collect rent from a new tenant, and still claim accelerated rent from MCO, without accounting for the rent received from the new tenant. Therefore, the accelerated rent clause bore no reasonable relationship to Cummings’s expected damages, rendering it an unenforceable penalty. The Appeals Court ruled that under these circumstances, Cummings could only collect its actual damages, not liquidated damages, from Hines under his guaranty.

Cummings has applied to the Supreme Judicial Court for further appellate review of this decision. Many commercial landlords and tenants, and their lawyers, will be watching with interest as to how the SJC rules on that application.

Download the article as seen in Banker & Tradesman on February 27, 2023. Learn more about Christopher R. Vaccaro.

For the helicopter parents among us, it’s worth noting that, these documents would be crucial if your child were unconscious, incapacitated or otherwise unable to make their own decisions. For parents of healthy kids, it’s hard for us to contemplate a scenario when these documents would be needed. Nevertheless, given life’s uncertainties, parents are best advised to speak with their adult children about these issues.

For the helicopter parents among us, it’s worth noting that, these documents would be crucial if your child were unconscious, incapacitated or otherwise unable to make their own decisions. For parents of healthy kids, it’s hard for us to contemplate a scenario when these documents would be needed. Nevertheless, given life’s uncertainties, parents are best advised to speak with their adult children about these issues.