Offshore Wind Projects Face Rising Challenges

Massachusetts law defines “Gateway municipalities” as those with populations between 35,000 and 250,000, where median household incomes and percentages of residents with bachelor’s degrees are below the state average.

Many are former manufacturing centers that offer “gateways” to better lives for lower income and immigrant families. Although the resort town of Barnstable fits the demographic requirements of a gateway municipality, it lacks the typical industrial history and immigrant cultures.

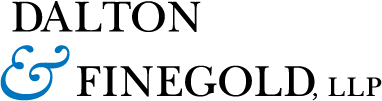

But as offshore wind turbine projects take root in federal waters south of Martha’s Vineyard, Barnstable is becoming the gateway for hundreds of megawatts of clean electrical energy.

Offshore wind energy is connected to the regional power grid through undersea cables. Barnstable’s coastline along Nantucket Sound is well-suited for cable landing sites.

There are three offshore wind projects in various stages of development and permitting that need cable landing sites in Barnstable – Vineyard Wind 1 with a landing site at Covell’s Beach, New England Wind 1 with a future landing site at Craigville Beach, and New England Wind 2 with a proposed landing site at Dowses Beach. Transmission lines will carry electricity to substations within Barnstable, then to the regional grid. Avangrid Renewables is behind these projects.

Offshore wind projects require numerous federal, state and local permits. Federal law requires environmental reviews by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers (USACE) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

In Massachusetts, the Department of Environmental Protection conducts its own project reviews, and the Energy Facilities Siting Board (EFSB), Department of Transportation, Department of Public Utilities and other state agencies also scrutinize these projects. Energy infrastructure lying within the borders of cities and towns requires wetlands orders of conditions and often zoning relief. Proponents are also expected to enter into host community agreements that provide economic benefits to municipalities that accommodate energy infrastructure.

Agreement Governs Relationship with Town

Vineyard Wind 1 has secured all required permits, and construction is underway 15 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard. The cable landing at Covell’s Beach and related onshore infrastructure is in place. The completed project is expected to generate 800 megawatts of electricity – enough for 400,000 homes. Damage to a turbine blade recently caused fiberglass shards to wash up on Cape and Islands beaches, delaying offshore construction, but there is optimism that this project will reach its full potential.

During the permitting process, Vineyard Wind 1 entered into a host community agreement (HCA) with Barnstable, providing assurances that the project will not harm the town’s public water supply. Perhaps more importantly, the HCA requires Vineyard Wind 1 to make payments to the town of up to $16 million, spread out over a 25-year period, in addition to ad valorem tax payments. In exchange, the town must support the project’s local permitting applications.

New England Wind 1 and 2 are going through separate permitting processes. Together they should generate 2,000 megawatts of electricity when complete. Both projects received BOEM approvals last year.

New England Wind 1 is further along in obtaining permits. It already has permits from the USACE and EPA. For state permits, New England Wind 1 has approval from the EFSB, and its environmental impact statement has been accepted, allowing the project to proceed with state permitting. The project proponent entered into an HCA with Barnstable in 2022, offering the town similar financial incentives to those offered to Vineyard Wind 1. New England Wind 1 construction is expected to begin this year.

Uncertain Financial Prospects for Industry

New England Wind 2’s future is less certain. This project suffered a setback last October, when the Barnstable Town Council voted to oppose the cable landing site at Dowses Beach. The non-binding vote leaves open the possibility of town council support for a different landing site in Barnstable. Perhaps another HCA with generous financial incentives can sweeten the pot enough to appease this opposition. Meanwhile, Avangrid Renewables continues to pursue state permits for New England Wind 2.

Offshore wind turbines projects have their challenges. Construction has stalled or halted on some projects, because of increased interest rates and costs, and supply chain difficulties. The newly-installed Trump administration is less supportive of clean energy projects than its predecessor, creating insecurity for an industry that relies heavily on government subsidies and tax credits, as well as offshore leases in federal waters.

Nevertheless, Vineyard Wind is now partially up and running, and New England Wind 1 seems likely to proceed. Although New England Wind 2 remains on the drawing board, Barnstable already plays an important role in meeting clean energy goals.

Download the article as seen in Banker & Tradesman on January 27, 2025. Learn more about Christopher R. Vaccaro.