Milton Vote Forces Legal Test of State’s Authority

By Christopher R. Vaccaro

Special to Banker & Tradesman

Massachusetts Attorney General Andrea Campbell’s recent lawsuit against the town of Milton shows that some of the state’s most powerful politicians will not tolerate cities and towns that fail to establish multi-family zoning districts required under the MBTA Communities law.

The MBTA Communities law, which became law in 2021, is intended to facilitate multifamily housing development in communities served by public transportation. The statute added a new Section 3A to the Zoning Act, applicable to “MBTA communities” – generally defined as municipalities with access to commuter rail, subway or ferry service, and those nearby.

There are 177 MBTA communities in eastern Massachusetts. The statute requires those communities to create at least one zoning district where multi-family housing is allowed as of right, without the need for variances or special permits. The districts must be near public transportation and allow at least 15 dwelling units per acre.

The Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities (EOHLC) published guidelines governing compliance with the statute. The guidelines recognize four classes of MBTA communities – rapid transit communities, commuter rail communities, adjacent communities (cities and larger towns without nearby transit stations) and adjacent small towns. Different requirements apply to each class. EOHLC expects all MBTA communities to adopt compliant zoning amendments over the next several months.

MBTA communities that fail to comply are ineligible to receive funding from 13 state programs; Those include the MassDevelopment Brownfields Redevelopment Fund; the MassWorks infrastructure program, which provides financial assistance for local infrastructure; and the HousingWorks infrastructure program, which provides grants and loans for rental housing projects. The effectiveness of these sanctions remains untested.

EOHLC classifies Milton as a rapid transit community because it hosts several stations along the Mattapan trolley line. EOHLC guidelines required that Milton establish by Dec. 31, 2023, a zoning district accommodating at least 2,461 multifamily housing units and having at least 50 acres.

Opposition Organized to Overturn Zoning Vote

Milton’s town government initially sought to comply with the statute. It obtained a $50,000 grant from EOHLC for consultants and community outreach. The Milton Select Board directed the Planning Department to develop an action plan. EOHLC later approved an additional $30,000 grant for the town to engage a consultant to draft a compliant zoning amendment.

Local opposition arose and organized itself. Many residents questioned EOHLC’s classification of Milton as a rapid transit community, the enforceability of EOHLC guidelines and whether Milton was legally required to comply with the statute. Nevertheless, Milton’s select board submitted a proposed zoning amendment to the planning board for review last September.

After several weeks and a public hearing, the Milton Planning Board recommended that the proposed amendment be returned to the Select Board for further study. Milton’s warrant committee made a similar recommendation. However, last December Milton’s town meeting overwhelmingly voted in favor of the proposed amendment. The opposition persisted, and successfully called for a referendum. Milton’s voters decisively voted against the amendment in February. EOHLC promptly notified Milton that it was not in compliance with the MBTA Communities law.

Lawsuit Follows Warnings

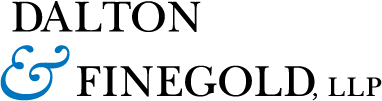

Attorney General Campbell has been clear that her office would insist that MBTA communities create multifamily housing districts. Last year she warned that noncompliant communities risked civil enforcement actions, and even possible liability under federal and state fair housing laws. Within two weeks after Milton’s referendum, she filed a lawsuit with the Supreme Judicial Court, alleging that Milton violated the statute. Her suit seeks a declaratory judgment that Milton failed to meet its obligations under the statute and EOHLC guidelines, and an injunction requiring Milton to adopt a compliant zoning amendment.

The attorney general’s lawsuit suggests that she will not wait to find out whether the loss of access to specific state funding programs will eventually persuade Milton to adopt compliant zoning. Her suit invokes Section 7 of the Zoning Act, which gives the Superior Court and Land Court jurisdiction to restrain zoning violations by injunction. Courts often use this power against property owners to enjoin zoning violations caused by non-compliant buildings and uses. The attorney general’s suit seeking an injunction forcing a municipality to adopt a specific zoning bylaw is unusual, but also unsurprising.

Milton residents have a choice. They can support expensive litigation with an attorney general determined to enforce the MBTA Communities Act, or they can dust off the zoning amendment approved by town meeting – take a deep breath – and support adoption of the amendment. Residents of other MBTA communities will be watching.

Download the article as seen in Banker & Tradesman on March 25, 2024. Learn more about Christopher R. Vaccaro.